13 November 2005

Service

of remembrance, in the Memorial Gardens, York, Sunday 13 November 2005.

I’ve

not joined the Remembrance Sunday commemorations in the city centre before.

Like many people of my generation – those of us of a left-wing tendency

anyway – I’ve often felt that the ceremonial part of it rather glorified

war. I always kept the two minutes’ silence, but never before with crowds

of other people who had gathered for that purpose. But I found it to be

a moving and thought-provoking morning.

I

arrived just before 11pm on the opposite side of the river, by Lendal Tower.

I’d lost track of the time, but the cannon fire from the memorial gardens

on the opposite bank certainly focussed my mind. It seems though that a

huge noise like that isn’t enough to bring everyone to attention. Most people

assembled on the riverbank fell quiet, observing the traditional silence,

but a group of women walking past us seemed totally oblivious, chattering

on.

Silence

seems an appropriate way to mark loss of life. That’s how you feel, when

you lose someone, like the world has stopped, or if it hasn’t, then it should.

All the frippery, clamour and racket of ordinary life should just cease,

for a while, in acknowledgement.

Usually,

for our particular and personal losses, it doesn’t. But when so many people

are lost at one time, silence is the only way to acknowledge the enormity

of it. The losses of war are so vast and so often pointless that we have

to keep on falling silent every year, in our ritual way, to realise how

many have died on our behalf, and in our name. And because we carry on going

to wars we have more and more war dead to remember.

After

the silence, there was another shot from a cannon, with associated ground-shaking,

accompanied by me jumping up a bit in the air, rather startled. I don’t think I was the only one.

People

started to move, heading towards the memorial gardens, where crowds were

already gathered, and where hymns were sung and prayers read.

Men

and women in military uniform were gathered around the memorial in the gardens,

while others were at the edge of the park, looking after what I assume was

the piece of military hardware that had fired just recently. As I’m such

an ignoramus it took me a while to realise this – I think that I was expecting

a cannon like those old-fashioned ones on ship’s decks, centuries ago.

There’s

a massive block of expensive new apartments next to the Memorial Gardens.

The side facing the gardens is full of balconies, and plants in pots, and

garden furniture. I looked up at it to see if any of the residents were

sharing in the event. There was one lady, of middle-age, looking

out from her high vantage point. All the other balconies seemed to be empty.

After the ceremony, the participants marched back towards the Eye of York, and many in the crowd, including me, followed.

It’s very difficult to walk alongside a loud marching band without starting

to walk in time, and once you start doing that, you want to start swinging

your arms too. I did resist the urge – as if you’re on your own, dressed

in casual clothes, it’s difficult to march in a military style without looking

a bit mad.

But

along Lendal, as I marched/walked past the end of an alleyway, a group of

young girls were gathered, and the nearest one to me broke into an enthusiastic

and rather cheerleader-like march, swinging her arms madly, and the other

girls joined in, all laughing. A

woman was looking out of a window at the Judge’s Lodgings, smiling. It all

seemed very jolly, probably as a result of the rousing music and the brightness

of the sunlit morning.

At

the end of Lendal, the sunshine was particularly bright in the open space

of St Helen’s Square, in front of the Mansion House. The Mayor and other

dignitaries were assembled on the steps. There were so many people gathered

that it was difficult to see the parade passing, and so I just stood behind

them, giving up the idea of taking any photos. Times like that I wish I

was very tall, instead of a shortie. I got a nice photo of the back of a

blonde woman’s head. And this photo of a policeman’s back.

Then above the music – which I think was the very jolly ‘Colonel Bogie’

– came the sound of applause, and I realised that the people around me were

making the sound – and that they were applauding the ex-servicemen who were

now passing in front of us. Over the shoulders of the people in front of

me I saw glimpses of the elderly gentlemen in their uniforms and in these

glimpses I was conscious of the different world they knew, and felt overwhelmed

for a moment and had to look down and pretend to fiddle with my camera for a while

until I regained my composure. It might be something to do with traditional British reserve, but I’ve never felt at ease with the idea of crying openly in a crowd full of strangers.

I

wonder what it’s like, to have lived through and fought through these wars

we remember today, and to see how the generations coming after haven’t always

respected the values you felt you were fighting for. In some ways we’ve progressed, in others we haven’t, but what you call progress does of course depend on your politics, and personal perspectives.

In

the 80s, when I was growing up, I couldn’t have joined the remembrance

day ceremonies. All I knew was that people around me seemed

to glorify war too much, and tabloid newspapers ran excited, supposedly patriotic

headlines about the Falklands conflict, and Margaret Thatcher seemed to

like being photographed on a tank.

But here we are in 2005, and I’m watching a ceremony for ex-servicemen and women, and in the face of their experiences my own views seem irrelevant. I am just an observer. As you get older I guess you can separate the politics from the personal, from the people who own the real stories. If I’d gone through the experience of fighting for my country, I’d expect some respect too. For all the violence I had to witness and the dirt and blood and watching my friends suffering around me.

So here in the city of York, in England, on a sunny November morning, it’s about the faces of the men

and women passing by in the parade, and the things they saw and carry with

them.

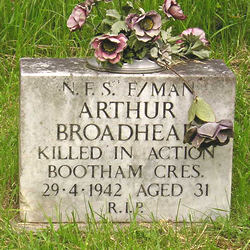

And not just those marching, but all those affected by war. People like my mother who were evacuated to live with families who perhaps weren’t always kind and welcoming. And her older female relatives, so many of whom had lost their husbands in the First World War. And the firefighters and others working here in the Second World War, trying to save burning buildings during the blitz on our largest cities and the Baedeker raid here in York. Like Arthur Broadhead, who was killed on the night of the raid, while working for the National Fire Service, and is buried in York

Cemetery.

Later

in the day I passed the war memorial on Station Rise. At the front of the

memorial were the poppy wreaths shown below, carefully and ceremoniously

placed in a neat line. Behind them, these flowers. Just the one bunch, placed

on the separate plaque set there after the Second World War. A handwritten

note was tucked underneath.

Two contrasting images symbolise the day for me, and what’s important now, here, in 2005. The war veterans who fought for freedom, dressed in their uniforms, passing the dark red front of the Mansion House. And the carefree teenage girls, larking around and laughing in a sunlit alleyway, enjoying it.

Thank you for adding a comment. Please note that comments are moderated, but should appear within 24 hours.