It’s the 11th day of the 11th month, a hundred years on from the start of the Great War, as they called it then, just afterwards, when it was supposed to end all wars and they didn’t realise we’d later call it the First World War to distinguish it from the Second World War. It seems appropriate to mention some relevant pages on this website. I’ve also been thinking a lot about how this year we’ve been part of a wider and more all-encompassing remembering.

The photo above is of a memorial window in the church at Hawnby, in North Yorkshire. I wrote about the church and its memorials on Remembrance Sunday a couple of years ago.

Isn’t it beautiful. Soul-stirring, a soldier with a face like an angel, lifting his eyes to heaven, on the battlefield. It is, I think, the kind of remembrance we prefer. We like our remembrance beautiful. I’ve been thinking a lot about this, this year.

Here’s the bigger picture, the other side of the window, which I mentioned when I wrote about it last time but didn’t include as an image.

Its strongly Christian theme is now obvious. I wonder, dear readers, if this makes you like it more, or less. Or if it changes your perception at all. Because of course religious imagery can be controversial. I’ve always been a little uncomfortable over the strong links between the church and the military, I don’t really understand it. But here I guess the message is supposed to be comforting. And the young soldier’s suffering brings him nearer to Christ.

The fighting parson of this church at Hawnby was keen for his sons to do their duty for king and country. He lost three sons in the war. Imagine that.

Every time I think about the fighting parson and his sons, I also think about the person who’s out of the picture in this heroic/manly story – the mother of those three young men. I’ve always wondered if she too was keen for her sons to go to war. I tend to imagine not. But then I think of Siegfried Sassoon’s poem, which reminds us that things aren’t always as we’d imagine them to be. Some women of the time did of course hand out white feathers to men who weren’t out fighting at the front. Perhaps the parson’s wife wanted her sons to be ‘heroes’ and bore her grief heroically when they didn’t come back. We don’t know what the parson’s wife thought. But this is what Sassoon thought:

Glory Of Women

You love us when we’re heroes, home on leave,

Or wounded in a mentionable place.

You worship decorations; you believe

That chivalry redeems the war’s disgrace.

You make us shells. You listen with delight,

By tales of dirt and danger fondly thrilled.

You crown our distant ardours while we fight,

And mourn our laurelled memories when we’re killed.

You can’t believe that British troops ‘retire’

When hell’s last horror breaks them, and they run,

Trampling the terrible corpses–blind with blood.

O German mother dreaming by the fire,

While you are knitting socks to send your son

His face is trodden deeper in the mud.

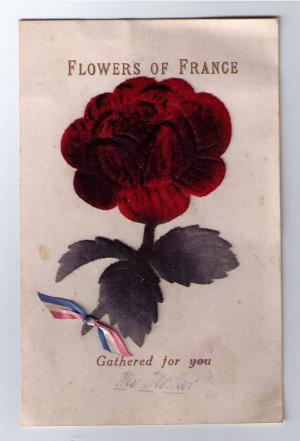

A postcard, found in York

A much smaller memorial. Not a memorial at all, really. Just a card, not a particularly grand or elaborate one. A card sent home by just one man, among so many other men, writing home to his mother. A century later it found its way to me, via my mother. Flowers of France, from a couple of years ago.

From beautiful delicate coloured glass to a fragile card to this far more substantial and now rather famous memorial, remembrance in stone.

Waggoners memorial, Sledmere

The Waggoners memorial, in Sledmere, East Yorkshire. (Not a misspelling – on the memorial itself it’s ‘waggoners’, with two gs, an older variant of the now more common spelling of ‘wagon’.)

We went for a walk in Sledmere on a beautiful May morning in 2006. The light on the memorial highlighted its ‘curiously homely’ carving, and I spent a while taking photos of it. This website was then a less regularly updated thing, as so many personal websites were, and it appears to have taken me a whole year to get together a page about it.

The growing interest in that old website page reflects the growing interest in the war this memorial commemorates. The page was online for years, generally unnoticed, not much visited.

I don’t obsessively look at my website stats to see what’s popular, but I do notice any peculiar spikes where a page suddenly gets a lot of visitors. One evening in January 2012 there was a sudden surge in the number of visitors to that page. Not coming via a link from Facebook, which is usually what causes a surge, but apparently all coming from Google searches, all slightly different (‘waggoners Sledmere’, ‘waggoners memorial’, ‘wolds waggoners’, etc). Clearly people all over the country were for some reason searching for the same thing. And because my waggoners page had been online for five years it came top in Google search results, hence the visitor increase. But why the sudden interest?

I realised it must have been mentioned in a popular TV or radio programme and looked on the BBC site to see if there had been a special programme on the memorial itself. Couldn’t find anything. Meanwhile they were still coming in, all those visitors, from their separate Googlings.

It was one of those moments in the life of a website where you’re suddenly reminded, having taken it for granted most of the time, of what an amazing thing it is, the internet. I was quite moved. I was also really curious.

As a last resort I thought ‘I wonder if Twitter can help’. I’d signed up for a Twitter account the previous autumn, tweeted about three times, then lost interest and not bothered with it. That evening I thought I’d log on again and try a search. It worked. A Twitter user who lives near Sledmere had mentioned in a tweet that the BBC’s One Show had included an item on the memorial that evening. Clearly immediately after seeing it the nation had rushed to Google to find out more. I realised that Twitter was quite useful really, and have been using it almost daily since.

This year, because of the centenary of the start of the First World War, the waggoners page has become one of this website’s most visited. I’ve had more requests about using its photos than I’ve had for any other page on this site. The photos taken on that morning in May eight years ago have been used by English Heritage in an exhibition in London and by several web-based educational resources. The centenary commemorations this year mean more of us know about those men from the Yorkshire Wolds farms and the part they played in the First World War.

A powerful image

A couple of days ago, Remembrance Sunday, I was looking at Twitter and saw one of the most moving images of war I’ve ever seen, attached to a tweet.

The tweet had the added words ‘Remembering the sacrifice & suffering of soldiers sent to fight on our behalf. #RemembranceDay #LestWeForget’.

I found the photo so moving because it illustrates what war does to the people doing the fighting, because it shows that war can make tough grown men want to curl up and cry like a child, and mainly because of the way the other soldier is cradling his colleague’s head with the kind of tenderness men don’t often show to one another. And of course because of the contrast provided by the third person, coldly remote, carrying on as normal.

So it is, and will remain for me, one of the most powerful examples of war photography I’ve ever seen.

But I didn’t retweet it, as I might usually do, because there was something not quite right.

Some of you will know already what the difficulty is. This isn’t an image of ‘our’ soldiers in the trenches in the First World War, or perhaps in the Second World War, as I think the person who tweeted it thought it was, as many seeing the photo maybe would think it was. These are US soldiers and this is an image from the Korean war.

It’s a photo by Al Chang, and it dates from 1950. It was well-known at the time. ‘The tableau of grief and comfort, taken in the Haktong-ni area of South Korea, became one of the enduring images of the Korean War’, states an article in the LA Times.

It took a while to trace this photo back to its source, and for that I have to thank the friend who managed to locate the original for me, as I couldn’t. I wanted to know the photographer’s name, and the context. I tried for some time to find it via a Google Images search, and saw many horrific images I wish I hadn’t. He managed to find the image on Flickr I’ve linked to above.

A good illustration of what happens all the time now to photographs online, cut and pasted away from any link with their original source and context, adrift from their creator. We wade our way through the muddied web, through misunderstandings and misinformation.

Does it matter? Maybe not. Interesting though. Perhaps, after all the commemoration this year, we now see all images like this as ‘in the trenches’.

This photo is one of those images reaching across from its particular time and its particular context. It does remind me of the sufferings of the men in the trenches of the First World War. To me, this is what war means. It isn’t just about those who died, it’s about what it did to the minds of those who lived. What it still does.

It reminds me that the First World War sent home a generation of men who were deeply damaged psychologically, who carried the horrors home with them but didn’t speak about it, who were always known to be ‘not quite right’ afterwards, carrying around that horror and distress in an age when men didn’t speak about these things.

Maybe men do now. I hope so. But that image to me is what war is, what it does to those who fight. It breaks people, in so many ways. Lest we forget.

And not just people. To close this rather long page, I want to bring it back home, to the local patch, with an image I’ve never forgotten. A photo I first saw many years back when browsing the online collection from the libraries and archives here in York. I’ve wanted to mention it many times over the years.

(c) City of York Council

It’s perhaps quite familiar now, maybe many people have seen it. Horses at what was the cattle market just outside the city walls, where the Barbican Centre now is. Horses rounded up to be sent to war. Poor dumb beasts, unaware.

When I first saw this photograph very few of us had thought about the role of horses in the war. I hadn’t. The focus on the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War has made us all more aware of many aspects of the conflict, educated us all in some way, and also embraced more widely than ever before all those caught up in that time of great suffering. Even the horses. At least we don’t send them off to war anymore.

Thank you for adding a comment. Please note that comments are moderated, but should appear within 24 hours.